How do you introduce a child to the esoteric concept of death? You probably don’t unless a granny or an uncle dies, or perhaps just as wrenching, a family pet. These are poignant teaching moments that a parent comfortable with the subject might use to illustrate mortality.

And then the questions arise: Where did Granny go? Is she asleep? Will Uncle Albert be waiting for us in heaven? Why didn’t Lobo come home from the vet’s office? Will I die someday? When will you die? Why do we have to die?

Children’s literature dealing with dying and death is a rich genre. From the modern classic The Tenth Good Thing About Barney by Judith Viorst, to a plethora of other age-appropriate stories such as The Invisible String by Patrice Karst and Nana Upstairs and Nana Downstairs by Tommy dePaola, there are numerous titles that can help children become aware of life’s realities while they try to make sense of their own feelings.

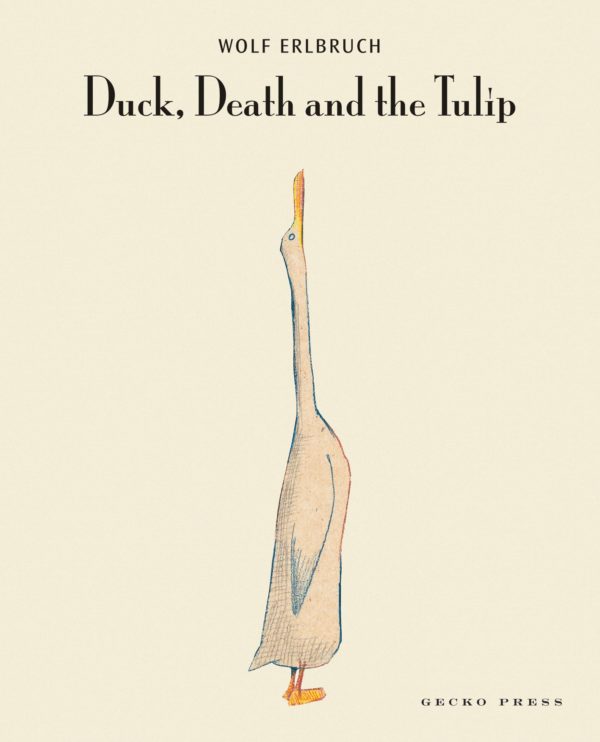

Without suggesting definitive answers, children’s book author and illustrator Wolf Erlbruch presents an intimate narrative in Duck, Death and the Tulip, a picture book of childlike brevity. Two characters encounter each other and tentatively form a friendly acquaintance. They check each other out and casually relax into conversation.

Death tells Duck that she was never alone. He has always been with her. Duck wants to know what happens next. Death is evasive. Who knows? They meander around all summer, taking a cold dip in the pond, climbing a tree to get a better view. This remove mimics the process of taking in the “big picture” as one ages; it puts the two above it all and makes Duck reflect on her new perspective:

“That’s what it will be like when I’m dead,” Duck thought. “The pond alone, without me.”

Death sometimes read minds. “When you’re dead, the pond will be gone, too — at least for you.”

“Are you sure?” Duck was astonished.

“As sure as can be,” Death said.

“That’s a comfort. I won’t have to mourn over it when…”

“…when you’re dead.” Death finished the sentence. He wasn’t coy about the subject.

The minimalist allegory sees the two friends—they have become friends—through the seasons until the chill of winter signals the coming end. When Duck exhales her last breath, Death carries her to the great river and tenderly sends her on her way.

The author’s subtle commentary, uniquely illustrated by two simple characters, draws you in. There’s no pathos, no emergency in their dialogue. Fantastic promises are not made; dramatic conclusions are not drawn. The message in this parable is unsentimental but sweet at the same time.

Through hearing of Duck’s encounter with Death, a child is allowed to wonder, to think about serious things without having to be told what they mean. This fits contemporary models of child psychology. Children are curious and impressionable. When bad things happen, such as the inexplicable loss of a loved one, they grieve as deeply as their elders might.

But given permission to do so, they—we all—learn to cope. In the story, we are left with the mystery unsolved, yet we need not be frightened—which might be the most refreshing aspect of this children’s picture book, an aspect not lost on the adult reading the tale to their young one.

An adult might, in fact, take comfort from Erlbruch’s gentle representation of death. His masterful intimation of life, longing, and dying is exquisite. It gives the reader, whatever their age, a possibility—that of acceptance of the natural cycles of life. And with acceptance, life becomes more precious and real.

“Wolf Erlbruch’s compelling visual language is an inspiration, garnering him a number of prizes and awards, including the 2006 Hans Christian Andersen Award from IBBY International. He treats his theme with gentleness, lightening the darkness that so often surrounds dying. He makes existential questions accessible and manageable for readers of all ages.” (From the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award)

~Ann Hutton