My eldest son was with us for the difficult duty of ending our geriatric cat’s suffering. We joined in profound grief and love and stood together in a hallowed place that only comes with goodbyes. I dug a hole, we buried the cat, said some words, and cried. He was far too young for this, I thought, but so was I.

A few bedtimes later, he put it together. He realized that we all die. That he, too, will die. He’s never been the same.

He began interrupting me as I read aloud to him to ask about the viability of creating a time machine that, at the moment of death, would return him to life as a new person. I told him certain people believe that that’s what happens, and there are religions that look forward to just that sort of arrangement. He said he didn’t believe in that and returned to obsessing on his time machine.

I could not fix this problem, the one for which the only solution is total surrender.

I became aware of my own inevitable expiration at around the same age as my son, and its horror is never more than a couple of sunny afternoons away. Like him, it has haunted and immobilized me. While I can now talk about death and I know that it’s not an inherently bad thing, it’s still the basis of my great sadness.

We bring one another uplifting news stories, mind-bending science, and fantastic photos. We lay around petting any one of our half dozen house animals, and together we revel in their generosity and their perfection.

My son is now a young man who brings up death very bluntly, citing technological breakthroughs that are imminent but which will manifest “after we’re dead.” He asked if I thought our dogs would die when he goes to college.

I miss the time when he knew the world was a fun and unlimited venue, when sadness was limited to a trivial and passing disappointment. As his father I have taken on the duty of reframing challenges so that they may be met head on. Of modeling strength as well as vulnerability, innovation as well as the humility required to ask for help.

My son knows about my unfulfilled dreams, my depression, my therapy, and my medication. He also knows how far I’ve come. He wants only for me to be happy and well. My ask is far more ambitious: I want to save him, but I can’t.

At the very moment we become a parent we agree to do everything in our power to make it better. That’s the moment we begin to fail.

I cannot save him. I can’t stop time.

I’m waiting for tests that will tell us if my cancer is still localized or if it’s grown to an area bigger than a breadbox. I’m experiencing a step up from my usual routine of darkness and worry. As for my eventual demise, I now struggle with the increased likelihood of it arriving sooner. I’m trying to be focused on good health and on the gifts in every moment, notions about which I’ve had a fairly good track record.

It’s not going very well. I love life and am trying to be grounded in gratitude and positivity. This has served me well in the past, but knowledge of this condition compounds my confusion, and I’ll try harder.

We’ve said goodbye to several pets over these past few years. Always crippling. Always sure that we won’t get any more animals.

We always do.

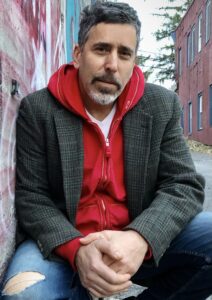

Seth David Branitz, author of The Trouble With Kim: On Transcending Despair and Approaching Joy, has been writing and recording songs as Seth Davis since 2001. He’s won multiple Moth Story Slams and Woodstock Story Slams, and has read his personal essays to audiences from Boston to Manhattan. He’s a founder of the organic café Karma Road in New Paltz, New York.